Table of Contents

- 15.1 Introduction to InnoDB

- 15.2 InnoDB and the ACID Model

- 15.3 InnoDB Multi-Versioning

- 15.4 InnoDB Architecture

- 15.5 InnoDB Locking and Transaction Model

- 15.6 InnoDB Configuration

- 15.6.1 InnoDB Startup Configuration

- 15.6.2 Configuring InnoDB for Read-Only Operation

- 15.6.3 InnoDB Buffer Pool Configuration

- 15.6.4 Configuring InnoDB Change Buffering

- 15.6.5 Configuring Thread Concurrency for InnoDB

- 15.6.6 Configuring the Number of Background InnoDB I/O Threads

- 15.6.7 Using Asynchronous I/O on Linux

- 15.6.8 Configuring the InnoDB Master Thread I/O Rate

- 15.6.9 Configuring Spin Lock Polling

- 15.6.10 Configuring InnoDB Purge Scheduling

- 15.6.11 Configuring Optimizer Statistics for InnoDB

- 15.6.12 Configuring the Merge Threshold for Index Pages

- 15.6.13 Enabling Automatic Configuration for a Dedicated MySQL Server

- 15.7 InnoDB Tablespaces

- 15.7.1 Resizing the InnoDB System Tablespace

- 15.7.2 Changing the Number or Size of InnoDB Redo Log Files

- 15.7.3 Using Raw Disk Partitions for the System Tablespace

- 15.7.4 InnoDB File-Per-Table Tablespaces

- 15.7.5 Creating File-Per-Table Tablespaces Outside the Data Directory

- 15.7.6 Copying File-Per-Table Tablespaces to Another Instance

- 15.7.7 Moving Tablespace Files While the Server is Offline

- 15.7.8 Configuring Undo Tablespaces

- 15.7.9 Truncating Undo Tablespaces

- 15.7.10 InnoDB General Tablespaces

- 15.7.11 InnoDB Tablespace Encryption

- 15.8 InnoDB Tables and Indexes

- 15.9 InnoDB Table and Page Compression

- 15.10 InnoDB Row Storage and Row Formats

- 15.11 InnoDB Disk I/O and File Space Management

- 15.12 InnoDB and Online DDL

- 15.13 InnoDB Startup Options and System Variables

- 15.14 InnoDB INFORMATION_SCHEMA Tables

- 15.14.1 InnoDB INFORMATION_SCHEMA Tables about Compression

- 15.14.2 InnoDB INFORMATION_SCHEMA Transaction and Locking Information

- 15.14.3 InnoDB INFORMATION_SCHEMA Schema Object Tables

- 15.14.4 InnoDB INFORMATION_SCHEMA FULLTEXT Index Tables

- 15.14.5 InnoDB INFORMATION_SCHEMA Buffer Pool Tables

- 15.14.6 InnoDB INFORMATION_SCHEMA Metrics Table

- 15.14.7 InnoDB INFORMATION_SCHEMA Temporary Table Info Table

- 15.14.8 Retrieving InnoDB Tablespace Metadata from INFORMATION_SCHEMA.FILES

- 15.15 InnoDB Integration with MySQL Performance Schema

- 15.16 InnoDB Monitors

- 15.17 InnoDB Backup and Recovery

- 15.18 InnoDB and MySQL Replication

- 15.19 InnoDB memcached Plugin

- 15.19.1 Benefits of the InnoDB memcached Plugin

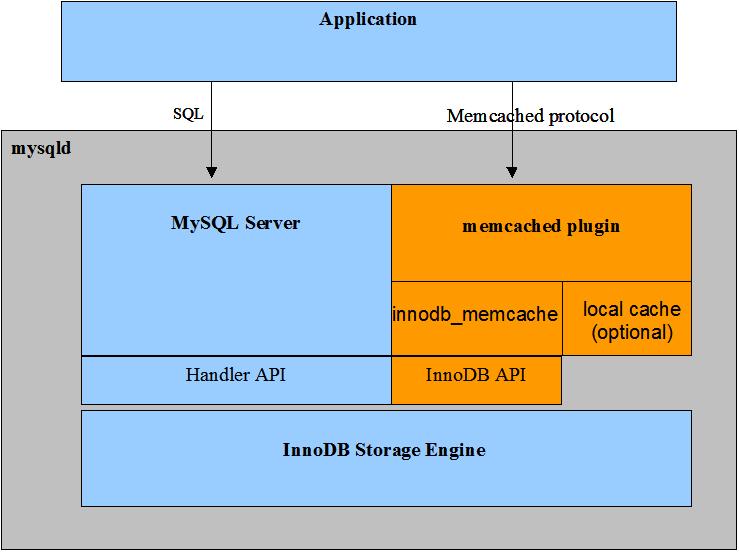

- 15.19.2 InnoDB memcached Architecture

- 15.19.3 Setting Up the InnoDB memcached Plugin

- 15.19.4 InnoDB memcached Multiple get and Range Query Support

- 15.19.5 Security Considerations for the InnoDB memcached Plugin

- 15.19.6 Writing Applications for the InnoDB memcached Plugin

- 15.19.7 The InnoDB memcached Plugin and Replication

- 15.19.8 InnoDB memcached Plugin Internals

- 15.19.9 Troubleshooting the InnoDB memcached Plugin

- 15.20 InnoDB Troubleshooting

InnoDB is a general-purpose storage engine that

balances high reliability and high performance. In MySQL

8.0, InnoDB is the default MySQL

storage engine. Unless you have configured a different default

storage engine, issuing a CREATE

TABLE statement without an ENGINE=

clause creates an InnoDB table.

Key Advantages of InnoDB

Its DML operations follow the ACID model, with transactions featuring commit, rollback, and crash-recovery capabilities to protect user data. See Section 15.2, “InnoDB and the ACID Model” for more information.

Row-level locking and Oracle-style consistent reads increase multi-user concurrency and performance. See Section 15.5, “InnoDB Locking and Transaction Model” for more information.

InnoDBtables arrange your data on disk to optimize queries based on primary keys. EachInnoDBtable has a primary key index called the clustered index that organizes the data to minimize I/O for primary key lookups. See Section 15.8.2.1, “Clustered and Secondary Indexes” for more information.To maintain data integrity,

InnoDBsupportsFOREIGN KEYconstraints. With foreign keys, inserts, updates, and deletes are checked to ensure they do not result in inconsistencies across different tables. See Section 15.8.1.6, “InnoDB and FOREIGN KEY Constraints” for more information.

Table 15.1 InnoDB Storage Engine Features

| Feature | Support |

|---|---|

| B-tree indexes | Yes |

| Backup/point-in-time recovery (Implemented in the server, rather than in the storage engine.) | Yes |

| Cluster database support | No |

| Clustered indexes | Yes |

| Compressed data | Yes |

| Data caches | Yes |

| Encrypted data (Implemented in the server via encryption functions. Data-at-rest tablespace encryption is available in MySQL 5.7 and later.) | Yes |

| Foreign key support | Yes |

| Full-text search indexes | Yes (InnoDB support for FULLTEXT indexes is available in MySQL 5.6 and later.) |

| Geospatial data type support | Yes |

| Geospatial indexing support | Yes (InnoDB support for geospatial indexing is available in MySQL 5.7 and later.) |

| Hash indexes | No (InnoDB utilizes hash indexes internally for its Adaptive Hash Index feature.) |

| Index caches | Yes |

| Locking granularity | Row |

| MVCC | Yes |

| Replication support (Implemented in the server, rather than in the storage engine.) | Yes |

| Storage limits | 64TB |

| T-tree indexes | No |

| Transactions | Yes |

| Update statistics for data dictionary | Yes |

To compare the features of InnoDB with other

storage engines provided with MySQL, see the Storage

Engine Features table in

Chapter 16, Alternative Storage Engines.

InnoDB Enhancements and New Features

For information about InnoDB enhancements and new

features, refer to:

The

InnoDBenhancements list in Section 1.4, “What Is New in MySQL 8.0”.The Release Notes.

Additional InnoDB Information and Resources

For

InnoDB-related terms and definitions, see the MySQL Glossary.For a forum dedicated to the

InnoDBstorage engine, see MySQL Forums::InnoDB.InnoDBis published under the same GNU GPL License Version 2 (of June 1991) as MySQL. For more information on MySQL licensing, see http://www.mysql.com/company/legal/licensing/.

You may find InnoDB tables beneficial for the

following reasons:

If your server crashes because of a hardware or software issue, regardless of what was happening in the database at the time, you don't need to do anything special after restarting the database.

InnoDBcrash recovery automatically finalizes any changes that were committed before the time of the crash, and undoes any changes that were in process but not committed. Just restart and continue where you left off.The

InnoDBstorage engine maintains its own buffer pool that caches table and index data in main memory as data is accessed. Frequently used data is processed directly from memory. This cache applies to many types of information and speeds up processing. On dedicated database servers, up to 80% of physical memory is often assigned to the buffer pool.If you split up related data into different tables, you can set up foreign keys that enforce referential integrity. Update or delete data, and the related data in other tables is updated or deleted automatically. Try to insert data into a secondary table without corresponding data in the primary table, and the bad data gets kicked out automatically.

If data becomes corrupted on disk or in memory, a checksum mechanism alerts you to the bogus data before you use it.

When you design your database with appropriate primary key columns for each table, operations involving those columns are automatically optimized. It is very fast to reference the primary key columns in

WHEREclauses,ORDER BYclauses,GROUP BYclauses, and join operations.Inserts, updates, and deletes are optimized by an automatic mechanism called change buffering.

InnoDBnot only allows concurrent read and write access to the same table, it caches changed data to streamline disk I/O.Performance benefits are not limited to giant tables with long-running queries. When the same rows are accessed over and over from a table, a feature called the Adaptive Hash Index takes over to make these lookups even faster, as if they came out of a hash table.

You can compress tables and associated indexes.

You can create and drop indexes with much less impact on performance and availability.

Truncating a file-per-table tablespace is very fast, and can free up disk space for the operating system to reuse, rather than freeing up space within the system tablespace that only

InnoDBcan reuse.The storage layout for table data is more efficient for

BLOBand long text fields, with the DYNAMIC row format.You can monitor the internal workings of the storage engine by querying INFORMATION_SCHEMA tables.

You can monitor the performance details of the storage engine by querying Performance Schema tables.

You can freely mix

InnoDBtables with tables from other MySQL storage engines, even within the same statement. For example, you can use a join operation to combine data fromInnoDBandMEMORYtables in a single query.InnoDBhas been designed for CPU efficiency and maximum performance when processing large data volumes.InnoDBtables can handle large quantities of data, even on operating systems where file size is limited to 2GB.

For InnoDB-specific tuning techniques you can

apply in your application code, see

Section 8.5, “Optimizing for InnoDB Tables”.

This section describes best practices when using

InnoDB tables.

Specifying a primary key for every table using the most frequently queried column or columns, or an auto-increment value if there is no obvious primary key.

Using joins wherever data is pulled from multiple tables based on identical ID values from those tables. For fast join performance, define foreign keys on the join columns, and declare those columns with the same data type in each table. Adding foreign keys ensures that referenced columns are indexed, which can improve performance. Foreign keys also propagate deletes or updates to all affected tables, and prevent insertion of data in a child table if the corresponding IDs are not present in the parent table.

Turning off autocommit. Committing hundreds of times a second puts a cap on performance (limited by the write speed of your storage device).

Grouping sets of related DML operations into transactions, by bracketing them with

START TRANSACTIONandCOMMITstatements. While you don't want to commit too often, you also don't want to issue huge batches ofINSERT,UPDATE, orDELETEstatements that run for hours without committing.Not using

LOCK TABLESstatements.InnoDBcan handle multiple sessions all reading and writing to the same table at once, without sacrificing reliability or high performance. To get exclusive write access to a set of rows, use theSELECT ... FOR UPDATEsyntax to lock just the rows you intend to update.Enabling the

innodb_file_per_tableoption or using general tablespaces to put the data and indexes for tables into separate files, instead of the system tablespace.The

innodb_file_per_tableoption is enabled by default.Evaluating whether your data and access patterns benefit from the

InnoDBtable or page compression features. You can compressInnoDBtables without sacrificing read/write capability.Running your server with the option

--sql_mode=NO_ENGINE_SUBSTITUTIONto prevent tables being created with a different storage engine if there is an issue with the engine specified in theENGINE=clause ofCREATE TABLE.

Issue the SHOW ENGINES statement to

view the available MySQL storage engines. Look for

DEFAULT in the InnoDB line.

mysql> SHOW ENGINES;

Alternatively, query the

INFORMATION_SCHEMA.ENGINES table.

mysql> SELECT * FROM INFORMATION_SCHEMA.ENGINES;

If InnoDB is not your default storage engine,

you can determine if your database server or applications work

correctly with InnoDB by restarting the server

with

--default-storage-engine=InnoDB

defined on the command line or with

default-storage-engine=innodb

defined in the [mysqld] section of your MySQL

server option file.

Since changing the default storage engine only affects new tables

as they are created, run all your application installation and

setup steps to confirm that everything installs properly. Then

exercise all the application features to make sure all the data

loading, editing, and querying features work. If a table relies on

a feature that is specific to another storage engine, you will

receive an error; add the

ENGINE=

clause to the other_engine_nameCREATE TABLE

statement to avoid the error.

If you did not make a deliberate decision about the storage

engine, and you want to preview how certain tables work when

created using InnoDB, issue the command

ALTER TABLE

table_name ENGINE=InnoDB; for each table. Or, to run

test queries and other statements without disturbing the original

table, make a copy:

CREATE TABLE InnoDB_Table (...) ENGINE=InnoDB AS SELECT * FROM other_engine_table;

To assess performance with a full application under a realistic workload, install the latest MySQL server and run benchmarks.

Test the full application lifecycle, from installation, through heavy usage, and server restart. Kill the server process while the database is busy to simulate a power failure, and verify that the data is recovered successfully when you restart the server.

Test any replication configurations, especially if you use different MySQL versions and options on the master and slaves.

The ACID model is a set of database

design principles that emphasize aspects of reliability that are

important for business data and mission-critical applications. MySQL

includes components such as the InnoDB storage

engine that adhere closely to the ACID model, so that data is not

corrupted and results are not distorted by exceptional conditions

such as software crashes and hardware malfunctions. When you rely on

ACID-compliant features, you do not need to reinvent the wheel of

consistency checking and crash recovery mechanisms. In cases where

you have additional software safeguards, ultra-reliable hardware, or

an application that can tolerate a small amount of data loss or

inconsistency, you can adjust MySQL settings to trade some of the

ACID reliability for greater performance or throughput.

The following sections discuss how MySQL features, in particular the

InnoDB storage engine, interact with the

categories of the ACID model:

A: atomicity.

C: consistency.

I:: isolation.

D: durability.

Atomicity

The atomicity aspect of the ACID

model mainly involves InnoDB

transactions. Related MySQL

features include:

Consistency

The consistency aspect of the ACID

model mainly involves internal InnoDB processing

to protect data from crashes. Related MySQL features include:

InnoDBdoublewrite buffer.InnoDBcrash recovery.

Isolation

The isolation aspect of the ACID

model mainly involves InnoDB

transactions, in particular

the isolation level that

applies to each transaction. Related MySQL features include:

Autocommit setting.

SET ISOLATION LEVELstatement.The low-level details of

InnoDBlocking. During performance tuning, you see these details throughINFORMATION_SCHEMAtables.

Durability

The durability aspect of the ACID model involves MySQL software features interacting with your particular hardware configuration. Because of the many possibilities depending on the capabilities of your CPU, network, and storage devices, this aspect is the most complicated to provide concrete guidelines for. (And those guidelines might take the form of buy “new hardware”.) Related MySQL features include:

InnoDBdoublewrite buffer, turned on and off by theinnodb_doublewriteconfiguration option.Configuration option

innodb_flush_log_at_trx_commit.Configuration option

sync_binlog.Configuration option

innodb_file_per_table.Write buffer in a storage device, such as a disk drive, SSD, or RAID array.

Battery-backed cache in a storage device.

The operating system used to run MySQL, in particular its support for the

fsync()system call.Uninterruptible power supply (UPS) protecting the electrical power to all computer servers and storage devices that run MySQL servers and store MySQL data.

Your backup strategy, such as frequency and types of backups, and backup retention periods.

For distributed or hosted data applications, the particular characteristics of the data centers where the hardware for the MySQL servers is located, and network connections between the data centers.

InnoDB is a

multi-versioned storage engine: it

keeps information about old versions of changed rows, to support

transactional features such as concurrency and

rollback. This information is

stored in the tablespace in a data structure called a

rollback segment (after

an analogous data structure in Oracle). InnoDB

uses the information in the rollback segment to perform the undo

operations needed in a transaction rollback. It also uses the

information to build earlier versions of a row for a

consistent read.

Internally, InnoDB adds three fields to each row

stored in the database. A 6-byte DB_TRX_ID field

indicates the transaction identifier for the last transaction that

inserted or updated the row. Also, a deletion is treated internally

as an update where a special bit in the row is set to mark it as

deleted. Each row also contains a 7-byte

DB_ROLL_PTR field called the roll pointer. The

roll pointer points to an undo log record written to the rollback

segment. If the row was updated, the undo log record contains the

information necessary to rebuild the content of the row before it

was updated. A 6-byte DB_ROW_ID field contains a

row ID that increases monotonically as new rows are inserted. If

InnoDB generates a clustered index automatically,

the index contains row ID values. Otherwise, the

DB_ROW_ID column does not appear in any index.

Undo logs in the rollback segment are divided into insert and update

undo logs. Insert undo logs are needed only in transaction rollback

and can be discarded as soon as the transaction commits. Update undo

logs are used also in consistent reads, but they can be discarded

only after there is no transaction present for which

InnoDB has assigned a snapshot that in a

consistent read could need the information in the update undo log to

build an earlier version of a database row.

Commit your transactions regularly, including those transactions

that issue only consistent reads. Otherwise,

InnoDB cannot discard data from the update undo

logs, and the rollback segment may grow too big, filling up your

tablespace.

The physical size of an undo log record in the rollback segment is typically smaller than the corresponding inserted or updated row. You can use this information to calculate the space needed for your rollback segment.

In the InnoDB multi-versioning scheme, a row is

not physically removed from the database immediately when you delete

it with an SQL statement. InnoDB only physically

removes the corresponding row and its index records when it discards

the update undo log record written for the deletion. This removal

operation is called a purge, and

it is quite fast, usually taking the same order of time as the SQL

statement that did the deletion.

If you insert and delete rows in smallish batches at about the same

rate in the table, the purge thread can start to lag behind and the

table can grow bigger and bigger because of all the

“dead” rows, making everything disk-bound and very

slow. In such a case, throttle new row operations, and allocate more

resources to the purge thread by tuning the

innodb_max_purge_lag system

variable. See Section 15.13, “InnoDB Startup Options and System Variables” for more

information.

InnoDB multiversion concurrency control (MVCC)

treats secondary indexes differently than clustered indexes.

Records in a clustered index are updated in-place, and their

hidden system columns point undo log entries from which earlier

versions of records can be reconstructed. Unlike clustered index

records, secondary index records do not contain hidden system

columns nor are they updated in-place.

When a secondary index column is updated, old secondary index

records are delete-marked, new records are inserted, and

delete-marked records are eventually purged. When a secondary

index record is delete-marked or the secondary index page is

updated by a newer transaction, InnoDB looks up

the database record in the clustered index. In the clustered

index, the record's DB_TRX_ID is checked, and

the correct version of the record is retrieved from the undo log

if the record was modified after the reading transaction was

initiated.

If a secondary index record is marked for deletion or the

secondary index page is updated by a newer transaction, the

covering index

technique is not used. Instead of returning values from the index

structure, InnoDB looks up the record in the

clustered index.

However, if the

index

condition pushdown (ICP) optimization is enabled, and parts

of the WHERE condition can be evaluated using

only fields from the index, the MySQL server still pushes this

part of the WHERE condition down to the storage

engine where it is evaluated using the index. If no matching

records are found, the clustered index lookup is avoided. If

matching records are found, even among delete-marked records,

InnoDB looks up the record in the clustered

index.

This section provides an introduction to the major components of the

InnoDB storage engine architecture.

The buffer pool is an area in main memory where

InnoDB caches table and index data as data is

accessed. The buffer pool allows frequently used data to be

processed directly from memory, which speeds up processing. On

dedicated database servers, up to 80% of physical memory is often

assigned to the InnoDB buffer pool.

For efficiency of high-volume read operations, the buffer pool is divided into pages that can potentially hold multiple rows. For efficiency of cache management, the buffer pool is implemented as a linked list of pages; data that is rarely used is aged out of the cache, using a variation of the LRU algorithm.

For more information, see Section 15.6.3.1, “The InnoDB Buffer Pool”, and Section 15.6.3, “InnoDB Buffer Pool Configuration”.

The change buffer is a special data structure that caches changes

to secondary index

pages when affected pages are not in the

buffer pool. The buffered

changes, which may result from

INSERT,

UPDATE, or

DELETE operations (DML), are merged

later when the pages are loaded into the buffer pool by other read

operations.

Unlike clustered indexes, secondary indexes are usually nonunique, and inserts into secondary indexes happen in a relatively random order. Similarly, deletes and updates may affect secondary index pages that are not adjacently located in an index tree. Merging cached changes at a later time, when affected pages are read into the buffer pool by other operations, avoids substantial random access I/O that would be required to read-in secondary index pages from disk.

Periodically, the purge operation that runs when the system is mostly idle, or during a slow shutdown, writes the updated index pages to disk. The purge operation can write disk blocks for a series of index values more efficiently than if each value were written to disk immediately.

Change buffer merging may take several hours when there are numerous secondary indexes to update and many affected rows. During this time, disk I/O is increased, which can cause a significant slowdown for disk-bound queries. Change buffer merging may also continue to occur after a transaction is committed. In fact, change buffer merging may continue to occur after a server shutdown and restart (see Section 15.20.2, “Forcing InnoDB Recovery” for more information).

In memory, the change buffer occupies part of the

InnoDB buffer pool. On disk, the change buffer

is part of the system tablespace, so that index changes remain

buffered across database restarts.

The type of data cached in the change buffer is governed by the

innodb_change_buffering

configuration option. For more information, see

Section 15.6.4, “Configuring InnoDB Change Buffering”. You can

also configure the maximum change buffer size. For more

information, see

Section 15.6.4.1, “Configuring the Change Buffer Maximum Size”.

Change buffering is not supported for a secondary index if the index contains a descending index column or if the primary key includes a descending index column.

The following options are available for change buffer monitoring:

InnoDBStandard Monitor output includes status information for the change buffer. To view monitor data, issue theSHOW ENGINE INNODB STATUScommand.mysql>

SHOW ENGINE INNODB STATUS\GChange buffer status information is located under the

INSERT BUFFER AND ADAPTIVE HASH INDEXheading and appears similar to the following:------------------------------------- INSERT BUFFER AND ADAPTIVE HASH INDEX ------------------------------------- Ibuf: size 1, free list len 0, seg size 2, 0 merges merged operations: insert 0, delete mark 0, delete 0 discarded operations: insert 0, delete mark 0, delete 0 Hash table size 4425293, used cells 32, node heap has 1 buffer(s) 13577.57 hash searches/s, 202.47 non-hash searches/s

For more information, see Section 15.16.3, “InnoDB Standard Monitor and Lock Monitor Output”.

The

INFORMATION_SCHEMA.INNODB_METRICStable provides most of the data points found inInnoDBStandard Monitor output, plus other data points. To view change buffer metrics and a description of each, issue the following query:mysql>

SELECT NAME, COMMENT FROM INFORMATION_SCHEMA.INNODB_METRICS WHERE NAME LIKE '%ibuf%'\GFor

INNODB_METRICStable usage information, see Section 15.14.6, “InnoDB INFORMATION_SCHEMA Metrics Table”.The

INFORMATION_SCHEMA.INNODB_BUFFER_PAGEtable provides metadata about each page in the buffer pool, including change buffer index and change buffer bitmap pages. Change buffer pages are identified byPAGE_TYPE.IBUF_INDEXis the page type for change buffer index pages, andIBUF_BITMAPis the page type for change buffer bitmap pages.WarningQuerying the

INNODB_BUFFER_PAGEtable can introduce significant performance overhead. To avoid impacting performance, reproduce the issue you want to investigate on a test instance and run your queries on the test instance.For example, you can query the

INNODB_BUFFER_PAGEtable to determine the approximate number ofIBUF_INDEXandIBUF_BITMAPpages as a percentage of total buffer pool pages.mysql>

SELECT (SELECT COUNT(*) FROM INFORMATION_SCHEMA.INNODB_BUFFER_PAGEWHERE PAGE_TYPE LIKE 'IBUF%') AS change_buffer_pages,(SELECT COUNT(*) FROM INFORMATION_SCHEMA.INNODB_BUFFER_PAGE) AS total_pages,(SELECT ((change_buffer_pages/total_pages)*100))AS change_buffer_page_percentage;+---------------------+-------------+-------------------------------+ | change_buffer_pages | total_pages | change_buffer_page_percentage | +---------------------+-------------+-------------------------------+ | 25 | 8192 | 0.3052 | +---------------------+-------------+-------------------------------+For information about other data provided by the

INNODB_BUFFER_PAGEtable, see Section 24.33.1, “The INFORMATION_SCHEMA INNODB_BUFFER_PAGE Table”. For related usage information, see Section 15.14.5, “InnoDB INFORMATION_SCHEMA Buffer Pool Tables”.Performance Schema provides change buffer mutex wait instrumentation for advanced performance monitoring. To view change buffer instrumentation, issue the following query:

mysql>

SELECT * FROM performance_schema.setup_instrumentsWHERE NAME LIKE '%wait/synch/mutex/innodb/ibuf%';+-------------------------------------------------------+---------+-------+ | NAME | ENABLED | TIMED | +-------------------------------------------------------+---------+-------+ | wait/synch/mutex/innodb/ibuf_bitmap_mutex | YES | YES | | wait/synch/mutex/innodb/ibuf_mutex | YES | YES | | wait/synch/mutex/innodb/ibuf_pessimistic_insert_mutex | YES | YES | +-------------------------------------------------------+---------+-------+For information about monitoring

InnoDBmutex waits, see Section 15.15.2, “Monitoring InnoDB Mutex Waits Using Performance Schema”.

The adaptive hash

index (AHI) lets InnoDB perform more

like an in-memory database on systems with appropriate

combinations of workload and ample memory for the

buffer pool, without

sacrificing any transactional features or reliability. This

feature is enabled by the

innodb_adaptive_hash_index

option, or turned off by

--skip-innodb_adaptive_hash_index at server

startup.

Based on the observed pattern of searches, MySQL builds a hash index using a prefix of the index key. The prefix of the key can be any length, and it may be that only some of the values in the B-tree appear in the hash index. Hash indexes are built on demand for those pages of the index that are often accessed.

If a table fits almost entirely in main memory, a hash index can

speed up queries by enabling direct lookup of any element, turning

the index value into a sort of pointer. InnoDB

has a mechanism that monitors index searches. If

InnoDB notices that queries could benefit from

building a hash index, it does so automatically.

With some workloads, the

speedup from hash index lookups greatly outweighs the extra work

to monitor index lookups and maintain the hash index structure.

Sometimes, the read/write lock that guards access to the adaptive

hash index can become a source of contention under heavy

workloads, such as multiple concurrent joins. Queries with

LIKE operators and %

wildcards also tend not to benefit from the AHI. For workloads

where the adaptive hash index is not needed, turning it off

reduces unnecessary performance overhead. Because it is difficult

to predict in advance whether this feature is appropriate for a

particular system, consider running benchmarks with it both

enabled and disabled, using a realistic workload. The

architectural changes in MySQL 5.6 and higher make more workloads

suitable for disabling the adaptive hash index than in earlier

releases, although it is still enabled by default.

The adaptive hash index search system is partitioned. Each index

is bound to a specific partition, and each partition is protected

by a separate latch. Partitioning is controlled by the

innodb_adaptive_hash_index_parts

configuration option. The

innodb_adaptive_hash_index_parts

option is set to 8 by default. The maximum setting is 512.

The hash index is always built based on an existing

B-tree index on the table.

InnoDB can build a hash index on a prefix of

any length of the key defined for the B-tree, depending on the

pattern of searches that InnoDB observes for

the B-tree index. A hash index can be partial, covering only those

pages of the index that are often accessed.

You can monitor the use of the adaptive hash index and the

contention for its use in the SEMAPHORES

section of the output of the

SHOW ENGINE INNODB

STATUS command. If you see many threads waiting on an

RW-latch created in btr0sea.c, then it might

be useful to disable adaptive hash indexing.

For more information about the performance characteristics of hash indexes, see Section 8.3.9, “Comparison of B-Tree and Hash Indexes”.

The redo log buffer is the memory area that holds data to be

written to the redo log. Redo

log buffer size is defined by the

innodb_log_buffer_size

configuration option. The redo log buffer is periodically flushed

to the log file on disk. A large redo log buffer enables large

transactions to run without the need to write redo log to disk

before the transactions commit. Thus, if you have transactions

that update, insert, or delete many rows, making the log buffer

larger saves disk I/O.

The

innodb_flush_log_at_trx_commit

option controls how the contents of the redo log buffer are

written to the log file. The

innodb_flush_log_at_timeout

option controls redo log flushing frequency.

The InnoDB system tablespace contains the

InnoDB data dictionary (metadata for

InnoDB-related objects) and is the storage area

for the doublewrite buffer, the change buffer, and undo logs. The

system tablespace also contains table and index data for any

user-created tables that are created in the system tablespace. The

system tablespace is considered a shared tablespace since it is

shared by multiple tables.

The system tablespace is represented by one or more data files. By

default, one system data file, named ibdata1,

is created in the MySQL data directory. The

size and number of system data files is controlled by the

innodb_data_file_path startup

option.

For related information, see Section 15.6.1, “InnoDB Startup Configuration”, and Section 15.7.1, “Resizing the InnoDB System Tablespace”.

The doublewrite buffer is a storage area located in the system

tablespace where InnoDB writes pages that are

flushed from the InnoDB buffer pool, before the

pages are written to their proper positions in the data file. Only

after flushing and writing pages to the doublewrite buffer, does

InnoDB write pages to their proper positions.

If there is an operating system, storage subsystem, or

mysqld process crash in the middle of a page

write, InnoDB can later find a good copy of the

page from the doublewrite buffer during crash recovery.

Although data is always written twice, the doublewrite buffer does

not require twice as much I/O overhead or twice as many I/O

operations. Data is written to the doublewrite buffer itself as a

large sequential chunk, with a single fsync()

call to the operating system.

The doublewrite buffer is enabled by default in most cases. To

disable the doublewrite buffer, set

innodb_doublewrite to 0.

If system tablespace files (“ibdata files”) are

located on Fusion-io devices that support atomic writes,

doublewrite buffering is automatically disabled and Fusion-io

atomic writes are used for all data files. Because the doublewrite

buffer setting is global, doublewrite buffering is also disabled

for data files residing on non-Fusion-io hardware. This feature is

only supported on Fusion-io hardware and is only enabled for

Fusion-io NVMFS on Linux. To take full advantage of this feature,

an innodb_flush_method setting of

O_DIRECT is recommended.

An undo log is a collection of undo log records associated with a single transaction. An undo log record contains information about how to undo the latest change by a transaction to a clustered index record. If another transaction needs to see the original data (as part of a consistent read operation), the unmodified data is retrieved from the undo log records. Undo logs exist within undo log segments, which are contained within rollback segments. Rollback segments reside in undo undo tablespaces and in the temporary tablespace. For more information about undo tablespaces, see Section 15.7.8, “Configuring Undo Tablespaces”. For information about multi-versioning, see Section 15.3, “InnoDB Multi-Versioning”.

The temporary tablespace and each undo tablespace individually

support a maximum of 128 rollback segments. The

innodb_rollback_segments

configuration option defines the number of rollback segments. Each

rollback segment supports up to 1023 concurrent data-modifying

transactions.

A file-per-table tablespace is a single-table tablespace that is

created in its own data file rather than in the system tablespace.

Tables are created in file-per-table tablespaces when the

innodb_file_per_table option is

enabled. Otherwise, InnoDB tables are created

in the system tablespace. Each file-per-table tablespace is

represented by a single .ibd data file, which

is created in the database directory by default.

File per-table tablespaces support DYNAMIC and

COMPRESSED row formats which support features

such as off-page storage for variable length data and table

compression. For information about these features, and about other

advantages of file-per-table tablespaces, see

Section 15.7.4, “InnoDB File-Per-Table Tablespaces”.

A shared InnoDB tablespace created using

CREATE TABLESPACE syntax. General

tablespaces can be created outside of the MySQL data directory,

are capable of holding multiple tables, and support tables of all

row formats.

Tables are added to a general tablespace using

CREATE TABLE

or

tbl_name ... TABLESPACE [=]

tablespace_nameALTER TABLE

syntax.

tbl_name TABLESPACE [=]

tablespace_name

For more information, see Section 15.7.10, “InnoDB General Tablespaces”.

An undo tablespace comprises one or more files that contain

undo logs. The number of undo

tablespaces used by InnoDB is defined by the

innodb_undo_tablespaces

configuration option. For more information, see

Section 15.7.8, “Configuring Undo Tablespaces”.

innodb_undo_tablespaces is

deprecated and will be removed in a future release.

User-created temporary tables and on-disk internal temporary

tables are created in a shared temporary tablespace. The

innodb_temp_data_file_path

configuration option defines the relative path, name, size, and

attributes for temporary tablespace data files. If no value is

specified for

innodb_temp_data_file_path, the

default behavior is to create an auto-extending data file named

ibtmp1 in the

innodb_data_home_dir directory

that is slightly larger than 12MB.

The temporary tablespace is removed on normal shutdown or on an aborted initialization, and is recreated each time the server is started. The temporary tablespace receives a dynamically generated space ID when it is created. Startup is refused if the temporary tablespace cannot be created. The temporary tablespace is not removed if the server halts unexpectedly. In this case, a database administrator can remove the temporary tablespace manually or restart the server, which removes and recreates the temporary tablespace automatically.

The temporary tablespace cannot reside on a raw device.

INFORMATION_SCHEMA.FILES provides

metadata about the InnoDB temporary tablespace.

Issue a query similar to this one to view temporary tablespace

metadata:

mysql> SELECT * FROM INFORMATION_SCHEMA.FILES WHERE TABLESPACE_NAME='innodb_temporary'\G

INFORMATION_SCHEMA.INNODB_TEMP_TABLE_INFO

provides metadata about user-created temporary tables that are

currently active within an InnoDB instance. For

more information, see

Section 15.14.7, “InnoDB INFORMATION_SCHEMA Temporary Table Info Table”.

By default, the temporary tablespace data file is autoextending and increases in size as necessary to accommodate on-disk temporary tables. For example, if an operation creates a temporary table that is 20MB in size, the temporary tablespace data file, which is 12MB in size by default when created, extends in size to accommodate it. When temporary tables are dropped, freed space can be reused for new temporary tables, but the data file remains at the extended size.

An autoextending temporary tablespace data file can become large in environments that use large temporary tables or that use temporary tables extensively. A large data file can also result from long running queries that use temporary tables.

To determine if a temporary tablespace data file is

autoextending, check the

innodb_temp_data_file_path

setting:

mysql> SELECT @@innodb_temp_data_file_path;

+------------------------------+

| @@innodb_temp_data_file_path |

+------------------------------+

| ibtmp1:12M:autoextend |

+------------------------------+

To check the size of temporary tablespace data files, query the

INFORMATION_SCHEMA.FILES table

using a query similar to this:

mysql>SELECT FILE_NAME, TABLESPACE_NAME, ENGINE, INITIAL_SIZE, TOTAL_EXTENTS*EXTENT_SIZEAS TotalSizeBytes, DATA_FREE, MAXIMUM_SIZE FROM INFORMATION_SCHEMA.FILESWHERE TABLESPACE_NAME = 'innodb_temporary'\G*************************** 1. row *************************** FILE_NAME: ./ibtmp1 TABLESPACE_NAME: innodb_temporary ENGINE: InnoDB INITIAL_SIZE: 12582912 TotalSizeBytes: 12582912 DATA_FREE: 6291456 MAXIMUM_SIZE: NULL

The TotalSizeBytes value reports the current

size of the temporary tablespace data file. For information

about other field values, see Section 24.9, “The INFORMATION_SCHEMA FILES Table”.

Alternatively, you can check the temporary tablespace data file

size on your operating system. By default, the temporary

tablespace data file is located in the directory defined by the

innodb_temp_data_file_path

configuration option. If a value was not specified for this

option explicitly, a temporary tablespace data file named

ibtmp1 is created in

innodb_data_home_dir, which

defaults to the MySQL data directory if unspecified.

To reclaim disk space occupied by a temporary tablespace data

file, you can restart the MySQL server. Restarting the server

removes and recreates the temporary tablespace data file

according to the attributes defined by

innodb_temp_data_file_path.

To prevent the temporary data file from becoming too large, you

can configure the

innodb_temp_data_file_path

option to specify a maximum file size. For example:

[mysqld] innodb_temp_data_file_path=ibtmp1:12M:autoextend:max:500M

When the data file reaches the maximum size, queries fail with

an error indicating that the table is full. Configuring

innodb_temp_data_file_path

requires restarting the server.

Alternatively, you can configure the

default_tmp_storage_engine and

internal_tmp_disk_storage_engine

options, which define the storage engine to use for user-created

and on-disk internal temporary tables, respectively. Both

options are set to InnoDB by default. The

MyISAM storage engine uses an individual file

for each temporary table, which is removed when the temporary

table is dropped.

Temporary table undo logs reside in the temporary tablespace and are used for temporary tables and related objects. Temporary table undo logs are not redo-logged, as they are not required for crash recovery. They are only used for rollback while the server is running. This special type of undo log benefits performance by avoiding redo logging I/O.

The innodb_rollback_segments

configuration option defines the number of rollback segments

used by the temporary tablespace.

The redo log is a disk-based data structure used during crash

recovery to correct data written by incomplete transactions.

During normal operations, the redo log encodes requests to change

InnoDB table data that result from SQL

statements or low-level API calls. Modifications that did not

finish updating the data files before an unexpected shutdown are

replayed automatically during initialization, and before the

connections are accepted. For information about the role of the

redo log in crash recovery, see Section 15.17.2, “InnoDB Recovery”.

By default, the redo log is physically represented on disk as a

set of files, named ib_logfile0 and

ib_logfile1. MySQL writes to the redo log

files in a circular fashion. Data in the redo log is encoded in

terms of records affected; this data is collectively referred to

as redo. The passage of data through the redo log is represented

by an ever-increasing LSN value.

For related information, see:

InnoDB, like any other

ACID-compliant database engine,

flushes the redo log of a

transaction before it is committed. InnoDB

uses group commit

functionality to group multiple such flush requests together to

avoid one flush for each commit. With group commit,

InnoDB issues a single write to the log file

to perform the commit action for multiple user transactions that

commit at about the same time, significantly improving

throughput.

For more information about performance of

COMMIT and other transactional operations,

see Section 8.5.2, “Optimizing InnoDB Transaction Management”.

To implement a large-scale, busy, or highly reliable database

application, to port substantial code from a different database

system, or to tune MySQL performance, it is important to understand

InnoDB locking and the InnoDB

transaction model.

This section discusses several topics related to

InnoDB locking and the InnoDB

transaction model with which you should be familiar.

Section 15.5.1, “InnoDB Locking” describes lock types used by

InnoDB.Section 15.5.2, “InnoDB Transaction Model” describes transaction isolation levels and the locking strategies used by each. It also discusses the use of

autocommit, consistent non-locking reads, and locking reads.Section 15.5.3, “Locks Set by Different SQL Statements in InnoDB” discusses specific types of locks set in

InnoDBfor various statements.Section 15.5.4, “Phantom Rows” describes how

InnoDBuses next-key locking to avoid phantom rows.Section 15.5.5, “Deadlocks in InnoDB” provides a deadlock example, discusses deadlock detection and rollback, and provides tips for minimizing and handling deadlocks in

InnoDB.

This section describes lock types used by

InnoDB.

InnoDB implements standard row-level locking

where there are two types of locks,

shared

(S) locks and

exclusive

(X) locks.

A shared (

S) lock permits the transaction that holds the lock to read a row.An exclusive (

X) lock permits the transaction that holds the lock to update or delete a row.

If transaction T1 holds a shared

(S) lock on row r,

then requests from some distinct transaction

T2 for a lock on row r are

handled as follows:

A request by

T2for anSlock can be granted immediately. As a result, bothT1andT2hold anSlock onr.A request by

T2for anXlock cannot be granted immediately.

If a transaction T1 holds an exclusive

(X) lock on row r,

a request from some distinct transaction T2

for a lock of either type on r cannot be

granted immediately. Instead, transaction T2

has to wait for transaction T1 to release its

lock on row r.

InnoDB supports multiple

granularity locking which permits coexistence of row

locks and table locks. For example, a statement such as

LOCK TABLES ...

WRITE takes an exclusive lock (an X

lock) on the specified table. To make locking at multiple

granularity levels practical, InnoDB uses

intention locks.

Intention locks are table-level locks that indicate which type

of lock (shared or exclusive) a transaction requires later for a

row in a table. There are two types of intention locks:

An intention shared lock (

IS) indicates that a transaction intends to set a shared lock on individual rows in a table.An intention exclusive lock (

IX) indicates that that a transaction intends to set an exclusive lock on individual rows in a table.

For example, SELECT ...

FOR SHARE sets an IS lock, and

SELECT ... FOR

UPDATE sets an IX lock.

The intention locking protocol is as follows:

Before a transaction can acquire a shared lock on a row in a table, it must first acquire an

ISlock or stronger on the table.Before a transaction can acquire an exclusive lock on a row in a table, it must first acquire an

IXlock on the table.

Table-level lock type compatibility is summarized in the following matrix.

X |

IX |

S |

IS |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

X |

Conflict | Conflict | Conflict | Conflict |

IX |

Conflict | Compatible | Conflict | Compatible |

S |

Conflict | Conflict | Compatible | Compatible |

IS |

Conflict | Compatible | Compatible | Compatible |

A lock is granted to a requesting transaction if it is compatible with existing locks, but not if it conflicts with existing locks. A transaction waits until the conflicting existing lock is released. If a lock request conflicts with an existing lock and cannot be granted because it would cause deadlock, an error occurs.

Intention locks do not block anything except full table requests

(for example, LOCK

TABLES ... WRITE). The main purpose of intention locks

is to show that someone is locking a row, or going to lock a row

in the table.

Transaction data for an intention lock appears similar to the

following in SHOW

ENGINE INNODB STATUS and

InnoDB monitor

output:

TABLE LOCK table `test`.`t` trx id 10080 lock mode IX

A record lock is a lock on an index record. For example,

SELECT c1 FROM t WHERE c1 = 10 FOR UPDATE;

prevents any other transaction from inserting, updating, or

deleting rows where the value of t.c1 is

10.

Record locks always lock index records, even if a table is

defined with no indexes. For such cases,

InnoDB creates a hidden clustered index and

uses this index for record locking. See

Section 15.8.2.1, “Clustered and Secondary Indexes”.

Transaction data for a record lock appears similar to the

following in SHOW

ENGINE INNODB STATUS and

InnoDB monitor

output:

RECORD LOCKS space id 58 page no 3 n bits 72 index `PRIMARY` of table `test`.`t` trx id 10078 lock_mode X locks rec but not gap Record lock, heap no 2 PHYSICAL RECORD: n_fields 3; compact format; info bits 0 0: len 4; hex 8000000a; asc ;; 1: len 6; hex 00000000274f; asc 'O;; 2: len 7; hex b60000019d0110; asc ;;

A gap lock is a lock on a gap between index records, or a lock

on the gap before the first or after the last index record. For

example, SELECT c1 FROM t WHERE c1 BETWEEN 10 and 20

FOR UPDATE; prevents other transactions from inserting

a value of 15 into column

t.c1, whether or not there was already any

such value in the column, because the gaps between all existing

values in the range are locked.

A gap might span a single index value, multiple index values, or even be empty.

Gap locks are part of the tradeoff between performance and concurrency, and are used in some transaction isolation levels and not others.

Gap locking is not needed for statements that lock rows using a

unique index to search for a unique row. (This does not include

the case that the search condition includes only some columns of

a multiple-column unique index; in that case, gap locking does

occur.) For example, if the id column has a

unique index, the following statement uses only an index-record

lock for the row having id value 100 and it

does not matter whether other sessions insert rows in the

preceding gap:

SELECT * FROM child WHERE id = 100;

If id is not indexed or has a nonunique

index, the statement does lock the preceding gap.

It is also worth noting here that conflicting locks can be held on a gap by different transactions. For example, transaction A can hold a shared gap lock (gap S-lock) on a gap while transaction B holds an exclusive gap lock (gap X-lock) on the same gap. The reason conflicting gap locks are allowed is that if a record is purged from an index, the gap locks held on the record by different transactions must be merged.

Gap locks in InnoDB are “purely

inhibitive”, which means they only stop other

transactions from inserting to the gap. They do not prevent

different transactions from taking gap locks on the same gap.

Thus, a gap X-lock has the same effect as a gap S-lock.

Gap locking can be disabled explicitly. This occurs if you

change the transaction isolation level to

READ COMMITTED. Under these

circumstances, gap locking is disabled for searches and index

scans and is used only for foreign-key constraint checking and

duplicate-key checking.

There are also other effects of using the

READ COMMITTED isolation

level. Record locks for nonmatching rows are released after

MySQL has evaluated the WHERE condition. For

UPDATE statements, InnoDB

does a “semi-consistent” read, such that it returns

the latest committed version to MySQL so that MySQL can

determine whether the row matches the WHERE

condition of the UPDATE.

A next-key lock is a combination of a record lock on the index record and a gap lock on the gap before the index record.

InnoDB performs row-level locking in such a

way that when it searches or scans a table index, it sets shared

or exclusive locks on the index records it encounters. Thus, the

row-level locks are actually index-record locks. A next-key lock

on an index record also affects the “gap” before

that index record. That is, a next-key lock is an index-record

lock plus a gap lock on the gap preceding the index record. If

one session has a shared or exclusive lock on record

R in an index, another session cannot insert

a new index record in the gap immediately before

R in the index order.

Suppose that an index contains the values 10, 11, 13, and 20. The possible next-key locks for this index cover the following intervals, where a round bracket denotes exclusion of the interval endpoint and a square bracket denotes inclusion of the endpoint:

(negative infinity, 10] (10, 11] (11, 13] (13, 20] (20, positive infinity)

For the last interval, the next-key lock locks the gap above the largest value in the index and the “supremum” pseudo-record having a value higher than any value actually in the index. The supremum is not a real index record, so, in effect, this next-key lock locks only the gap following the largest index value.

By default, InnoDB operates in

REPEATABLE READ transaction

isolation level. In this case, InnoDB uses

next-key locks for searches and index scans, which prevents

phantom rows (see Section 15.5.4, “Phantom Rows”).

Transaction data for a next-key lock appears similar to the

following in SHOW

ENGINE INNODB STATUS and

InnoDB monitor

output:

RECORD LOCKS space id 58 page no 3 n bits 72 index `PRIMARY` of table `test`.`t` trx id 10080 lock_mode X Record lock, heap no 1 PHYSICAL RECORD: n_fields 1; compact format; info bits 0 0: len 8; hex 73757072656d756d; asc supremum;; Record lock, heap no 2 PHYSICAL RECORD: n_fields 3; compact format; info bits 0 0: len 4; hex 8000000a; asc ;; 1: len 6; hex 00000000274f; asc 'O;; 2: len 7; hex b60000019d0110; asc ;;

An insert intention lock is a type of gap lock set by

INSERT operations prior to row

insertion. This lock signals the intent to insert in such a way

that multiple transactions inserting into the same index gap

need not wait for each other if they are not inserting at the

same position within the gap. Suppose that there are index

records with values of 4 and 7. Separate transactions that

attempt to insert values of 5 and 6, respectively, each lock the

gap between 4 and 7 with insert intention locks prior to

obtaining the exclusive lock on the inserted row, but do not

block each other because the rows are nonconflicting.

The following example demonstrates a transaction taking an insert intention lock prior to obtaining an exclusive lock on the inserted record. The example involves two clients, A and B.

Client A creates a table containing two index records (90 and 102) and then starts a transaction that places an exclusive lock on index records with an ID greater than 100. The exclusive lock includes a gap lock before record 102:

mysql>CREATE TABLE child (id int(11) NOT NULL, PRIMARY KEY(id)) ENGINE=InnoDB;mysql>INSERT INTO child (id) values (90),(102);mysql>START TRANSACTION;mysql>SELECT * FROM child WHERE id > 100 FOR UPDATE;+-----+ | id | +-----+ | 102 | +-----+

Client B begins a transaction to insert a record into the gap. The transaction takes an insert intention lock while it waits to obtain an exclusive lock.

mysql>START TRANSACTION;mysql>INSERT INTO child (id) VALUES (101);

Transaction data for an insert intention lock appears similar to

the following in

SHOW ENGINE INNODB

STATUS and

InnoDB monitor

output:

RECORD LOCKS space id 31 page no 3 n bits 72 index `PRIMARY` of table `test`.`child`

trx id 8731 lock_mode X locks gap before rec insert intention waiting

Record lock, heap no 3 PHYSICAL RECORD: n_fields 3; compact format; info bits 0

0: len 4; hex 80000066; asc f;;

1: len 6; hex 000000002215; asc " ;;

2: len 7; hex 9000000172011c; asc r ;;...

An AUTO-INC lock is a special table-level

lock taken by transactions inserting into tables with

AUTO_INCREMENT columns. In the simplest case,

if one transaction is inserting values into the table, any other

transactions must wait to do their own inserts into that table,

so that rows inserted by the first transaction receive

consecutive primary key values.

The innodb_autoinc_lock_mode

configuration option controls the algorithm used for

auto-increment locking. It allows you to choose how to trade off

between predictable sequences of auto-increment values and

maximum concurrency for insert operations.

For more information, see Section 15.8.1.5, “AUTO_INCREMENT Handling in InnoDB”.

InnoDB supports SPATIAL

indexing of columns containing spatial columns (see

Section 11.5.9, “Optimizing Spatial Analysis”).

To handle locking for operations involving

SPATIAL indexes, next-key locking does not

work well to support REPEATABLE

READ or

SERIALIZABLE transaction

isolation levels. There is no absolute ordering concept in

multidimensional data, so it is not clear which is the

“next” key.

To enable support of isolation levels for tables with

SPATIAL indexes, InnoDB

uses predicate locks. A SPATIAL index

contains minimum bounding rectangle (MBR) values, so

InnoDB enforces consistent read on the index

by setting a predicate lock on the MBR value used for a query.

Other transactions cannot insert or modify a row that would

match the query condition.

In the InnoDB transaction model, the goal is to

combine the best properties of a

multi-versioning database with

traditional two-phase locking. InnoDB performs

locking at the row level and runs queries as nonlocking

consistent reads by

default, in the style of Oracle. The lock information in

InnoDB is stored space-efficiently so that lock

escalation is not needed. Typically, several users are permitted

to lock every row in InnoDB tables, or any

random subset of the rows, without causing

InnoDB memory exhaustion.

Transaction isolation is one of the foundations of database processing. Isolation is the I in the acronym ACID; the isolation level is the setting that fine-tunes the balance between performance and reliability, consistency, and reproducibility of results when multiple transactions are making changes and performing queries at the same time.

InnoDB offers all four transaction isolation

levels described by the SQL:1992 standard:

READ UNCOMMITTED,

READ COMMITTED,

REPEATABLE READ, and

SERIALIZABLE. The default

isolation level for InnoDB is

REPEATABLE READ.

A user can change the isolation level for a single session or

for all subsequent connections with the SET

TRANSACTION statement. To set the server's default

isolation level for all connections, use the

--transaction-isolation option on

the command line or in an option file. For detailed information

about isolation levels and level-setting syntax, see

Section 13.3.7, “SET TRANSACTION Syntax”.

InnoDB supports each of the transaction

isolation levels described here using different

locking strategies. You can

enforce a high degree of consistency with the default

REPEATABLE READ level, for

operations on crucial data where

ACID compliance is important.

Or you can relax the consistency rules with

READ COMMITTED or even

READ UNCOMMITTED, in

situations such as bulk reporting where precise consistency and

repeatable results are less important than minimizing the amount

of overhead for locking.

SERIALIZABLE enforces even

stricter rules than REPEATABLE

READ, and is used mainly in specialized situations,

such as with XA transactions and

for troubleshooting issues with concurrency and

deadlocks.

The following list describes how MySQL supports the different transaction levels. The list goes from the most commonly used level to the least used.

This is the default isolation level for

InnoDB. Consistent reads within the same transaction read the snapshot established by the first read. This means that if you issue several plain (nonlocking)SELECTstatements within the same transaction, theseSELECTstatements are consistent also with respect to each other. See Section 15.5.2.3, “Consistent Nonlocking Reads”.For locking reads (

SELECTwithFOR UPDATEorFOR SHARE),UPDATE, andDELETEstatements, locking depends on whether the statement uses a unique index with a unique search condition, or a range-type search condition.For a unique index with a unique search condition,

InnoDBlocks only the index record found, not the gap before it.For other search conditions,

InnoDBlocks the index range scanned, using gap locks or next-key locks to block insertions by other sessions into the gaps covered by the range. For information about gap locks and next-key locks, see Section 15.5.1, “InnoDB Locking”.

Each consistent read, even within the same transaction, sets and reads its own fresh snapshot. For information about consistent reads, see Section 15.5.2.3, “Consistent Nonlocking Reads”.

For locking reads (

SELECTwithFOR UPDATEorFOR SHARE),UPDATEstatements, andDELETEstatements,InnoDBlocks only index records, not the gaps before them, and thus permits the free insertion of new records next to locked records. Gap locking is only used for foreign-key constraint checking and duplicate-key checking.Because gap locking is disabled, phantom problems may occur, as other sessions can insert new rows into the gaps. For information about phantoms, see Section 15.5.4, “Phantom Rows”.

Only row-based binary logging is supported with the

READ COMMITTEDisolation level. If you useREAD COMMITTEDwithbinlog_format=MIXED, the server automatically uses row-based logging.Using

READ COMMITTEDhas additional effects:For

UPDATEorDELETEstatements,InnoDBholds locks only for rows that it updates or deletes. Record locks for nonmatching rows are released after MySQL has evaluated theWHEREcondition. This greatly reduces the probability of deadlocks, but they can still happen.For

UPDATEstatements, if a row is already locked,InnoDBperforms a “semi-consistent” read, returning the latest committed version to MySQL so that MySQL can determine whether the row matches theWHEREcondition of theUPDATE. If the row matches (must be updated), MySQL reads the row again and this timeInnoDBeither locks it or waits for a lock on it.

Consider the following example, beginning with this table:

CREATE TABLE t (a INT NOT NULL, b INT) ENGINE = InnoDB; INSERT INTO t VALUES (1,2),(2,3),(3,2),(4,3),(5,2); COMMIT;

In this case, the table has no indexes, so searches and index scans use the hidden clustered index for record locking (see Section 15.8.2.1, “Clustered and Secondary Indexes”) rather than indexed columns.

Suppose that one session performs an

UPDATEusing these statements:# Session A START TRANSACTION; UPDATE t SET b = 5 WHERE b = 3;

Suppose also that a second session performs an

UPDATEby executing these statements following those of the first session:# Session B UPDATE t SET b = 4 WHERE b = 2;

As

InnoDBexecutes eachUPDATE, it first acquires an exclusive lock for each row, and then determines whether to modify it. IfInnoDBdoes not modify the row, it releases the lock. Otherwise,InnoDBretains the lock until the end of the transaction. This affects transaction processing as follows.When using the default

REPEATABLE READisolation level, the firstUPDATEacquires an x-lock on each row that it reads and does not release any of them:x-lock(1,2); retain x-lock x-lock(2,3); update(2,3) to (2,5); retain x-lock x-lock(3,2); retain x-lock x-lock(4,3); update(4,3) to (4,5); retain x-lock x-lock(5,2); retain x-lock

The second

UPDATEblocks as soon as it tries to acquire any locks (because first update has retained locks on all rows), and does not proceed until the firstUPDATEcommits or rolls back:x-lock(1,2); block and wait for first UPDATE to commit or roll back

If

READ COMMITTEDis used instead, the firstUPDATEacquires an x-lock on each row that it reads and releases those for rows that it does not modify:x-lock(1,2); unlock(1,2) x-lock(2,3); update(2,3) to (2,5); retain x-lock x-lock(3,2); unlock(3,2) x-lock(4,3); update(4,3) to (4,5); retain x-lock x-lock(5,2); unlock(5,2)

For the second

UPDATE,InnoDBdoes a “semi-consistent” read, returning the latest committed version of each row that it reads to MySQL so that MySQL can determine whether the row matches theWHEREcondition of theUPDATE:x-lock(1,2); update(1,2) to (1,4); retain x-lock x-lock(2,3); unlock(2,3) x-lock(3,2); update(3,2) to (3,4); retain x-lock x-lock(4,3); unlock(4,3) x-lock(5,2); update(5,2) to (5,4); retain x-lock

However, if the

WHEREcondition includes an indexed column, andInnoDBuses the index, only the indexed column is considered when taking and retaining record locks. In the following example, the firstUPDATEtakes and retains an x-lock on each row where b = 2. The secondUPDATEblocks when it tries to acquire x-locks on the same records, as it also uses the index defined on column b.CREATE TABLE t (a INT NOT NULL, b INT, c INT, INDEX (b)) ENGINE = InnoDB; INSERT INTO t VALUES (1,2,3),(2,2,4); COMMIT; # Session A START TRANSACTION; UPDATE t SET b = 3 WHERE b = 2 AND c = 3; # Session B UPDATE t SET b = 4 WHERE b = 2 AND c = 4;

The effects of using the

READ COMMITTEDisolation level are the same as enabling the deprecatedinnodb_locks_unsafe_for_binlogconfiguration option, with these exceptions:Enabling

innodb_locks_unsafe_for_binlogis a global setting and affects all sessions, whereas the isolation level can be set globally for all sessions, or individually per session.innodb_locks_unsafe_for_binlogcan be set only at server startup, whereas the isolation level can be set at startup or changed at runtime.

READ COMMITTEDtherefore offers finer and more flexible control thaninnodb_locks_unsafe_for_binlog.SELECTstatements are performed in a nonlocking fashion, but a possible earlier version of a row might be used. Thus, using this isolation level, such reads are not consistent. This is also called a dirty read. Otherwise, this isolation level works likeREAD COMMITTED.This level is like

REPEATABLE READ, butInnoDBimplicitly converts all plainSELECTstatements toSELECT ... FOR SHAREifautocommitis disabled. Ifautocommitis enabled, theSELECTis its own transaction. It therefore is known to be read only and can be serialized if performed as a consistent (nonlocking) read and need not block for other transactions. (To force a plainSELECTto block if other transactions have modified the selected rows, disableautocommit.)

In InnoDB, all user activity occurs inside a

transaction. If autocommit mode

is enabled, each SQL statement forms a single transaction on its

own. By default, MySQL starts the session for each new

connection with autocommit

enabled, so MySQL does a commit after each SQL statement if that

statement did not return an error. If a statement returns an

error, the commit or rollback behavior depends on the error. See

Section 15.20.4, “InnoDB Error Handling”.

A session that has autocommit

enabled can perform a multiple-statement transaction by starting

it with an explicit

START

TRANSACTION or

BEGIN

statement and ending it with a

COMMIT or

ROLLBACK

statement. See Section 13.3.1, “START TRANSACTION, COMMIT, and ROLLBACK Syntax”.

If autocommit mode is disabled

within a session with SET autocommit = 0, the

session always has a transaction open. A

COMMIT or

ROLLBACK

statement ends the current transaction and a new one starts.

If a session that has

autocommit disabled ends

without explicitly committing the final transaction, MySQL rolls

back that transaction.

Some statements implicitly end a transaction, as if you had done

a COMMIT before executing the

statement. For details, see Section 13.3.3, “Statements That Cause an Implicit Commit”.

A COMMIT means that the changes

made in the current transaction are made permanent and become

visible to other sessions. A

ROLLBACK

statement, on the other hand, cancels all modifications made by

the current transaction. Both

COMMIT and

ROLLBACK

release all InnoDB locks that were set during

the current transaction.

By default, connection to the MySQL server begins with autocommit mode enabled, which automatically commits every SQL statement as you execute it. This mode of operation might be unfamiliar if you have experience with other database systems, where it is standard practice to issue a sequence of DML statements and commit them or roll them back all together.

To use multiple-statement

transactions, switch

autocommit off with the SQL statement SET autocommit

= 0 and end each transaction with

COMMIT or

ROLLBACK as

appropriate. To leave autocommit on, begin each transaction

with START

TRANSACTION and end it with

COMMIT or

ROLLBACK.

The following example shows two transactions. The first is

committed; the second is rolled back.

shell> mysql test

mysql>CREATE TABLE customer (a INT, b CHAR (20), INDEX (a));Query OK, 0 rows affected (0.00 sec) mysql>-- Do a transaction with autocommit turned on.mysql>START TRANSACTION;Query OK, 0 rows affected (0.00 sec) mysql>INSERT INTO customer VALUES (10, 'Heikki');Query OK, 1 row affected (0.00 sec) mysql>COMMIT;Query OK, 0 rows affected (0.00 sec) mysql>-- Do another transaction with autocommit turned off.mysql>SET autocommit=0;Query OK, 0 rows affected (0.00 sec) mysql>INSERT INTO customer VALUES (15, 'John');Query OK, 1 row affected (0.00 sec) mysql>INSERT INTO customer VALUES (20, 'Paul');Query OK, 1 row affected (0.00 sec) mysql>DELETE FROM customer WHERE b = 'Heikki';Query OK, 1 row affected (0.00 sec) mysql>-- Now we undo those last 2 inserts and the delete.mysql>ROLLBACK;Query OK, 0 rows affected (0.00 sec) mysql>SELECT * FROM customer;+------+--------+ | a | b | +------+--------+ | 10 | Heikki | +------+--------+ 1 row in set (0.00 sec) mysql>

Transactions in Client-Side Languages

In APIs such as PHP, Perl DBI, JDBC, ODBC, or the standard C

call interface of MySQL, you can send transaction control

statements such as COMMIT to

the MySQL server as strings just like any other SQL statements

such as SELECT or

INSERT. Some APIs also offer

separate special transaction commit and rollback functions or

methods.

A consistent read

means that InnoDB uses multi-versioning to

present to a query a snapshot of the database at a point in

time. The query sees the changes made by transactions that

committed before that point of time, and no changes made by

later or uncommitted transactions. The exception to this rule is

that the query sees the changes made by earlier statements

within the same transaction. This exception causes the following

anomaly: If you update some rows in a table, a

SELECT sees the latest version of

the updated rows, but it might also see older versions of any

rows. If other sessions simultaneously update the same table,

the anomaly means that you might see the table in a state that

never existed in the database.

If the transaction

isolation level is

REPEATABLE READ (the default

level), all consistent reads within the same transaction read

the snapshot established by the first such read in that

transaction. You can get a fresher snapshot for your queries by

committing the current transaction and after that issuing new

queries.

With READ COMMITTED isolation

level, each consistent read within a transaction sets and reads

its own fresh snapshot.

Consistent read is the default mode in which

InnoDB processes

SELECT statements in

READ COMMITTED and

REPEATABLE READ isolation

levels. A consistent read does not set any locks on the tables

it accesses, and therefore other sessions are free to modify

those tables at the same time a consistent read is being

performed on the table.

Suppose that you are running in the default

REPEATABLE READ isolation

level. When you issue a consistent read (that is, an ordinary

SELECT statement),

InnoDB gives your transaction a timepoint

according to which your query sees the database. If another

transaction deletes a row and commits after your timepoint was

assigned, you do not see the row as having been deleted. Inserts

and updates are treated similarly.

The snapshot of the database state applies to

SELECT statements within a

transaction, not necessarily to

DML statements. If you insert

or modify some rows and then commit that transaction, a

DELETE or

UPDATE statement issued from

another concurrent REPEATABLE READ

transaction could affect those just-committed rows, even

though the session could not query them. If a transaction does

update or delete rows committed by a different transaction,

those changes do become visible to the current transaction.

For example, you might encounter a situation like the

following:

SELECT COUNT(c1) FROM t1 WHERE c1 = 'xyz'; -- Returns 0: no rows match. DELETE FROM t1 WHERE c1 = 'xyz'; -- Deletes several rows recently committed by other transaction. SELECT COUNT(c2) FROM t1 WHERE c2 = 'abc'; -- Returns 0: no rows match. UPDATE t1 SET c2 = 'cba' WHERE c2 = 'abc'; -- Affects 10 rows: another txn just committed 10 rows with 'abc' values. SELECT COUNT(c2) FROM t1 WHERE c2 = 'cba'; -- Returns 10: this txn can now see the rows it just updated.

You can advance your timepoint by committing your transaction

and then doing another SELECT or

START TRANSACTION WITH

CONSISTENT SNAPSHOT.

This is called multi-versioned concurrency control.

In the following example, session A sees the row inserted by B only when B has committed the insert and A has committed as well, so that the timepoint is advanced past the commit of B.

Session A Session B

SET autocommit=0; SET autocommit=0;

time

| SELECT * FROM t;

| empty set

| INSERT INTO t VALUES (1, 2);

|

v SELECT * FROM t;

empty set

COMMIT;

SELECT * FROM t;

empty set

COMMIT;

SELECT * FROM t;

---------------------

| 1 | 2 |

---------------------

If you want to see the “freshest” state of the

database, use either the READ

COMMITTED isolation level or a

locking read:

SELECT * FROM t FOR SHARE;

With READ COMMITTED isolation

level, each consistent read within a transaction sets and reads

its own fresh snapshot. With FOR SHARE, a

locking read occurs instead: A SELECT blocks

until the transaction containing the freshest rows ends (see

Section 15.5.2.4, “Locking Reads”).

Consistent read does not work over certain DDL statements:

Consistent read does not work over